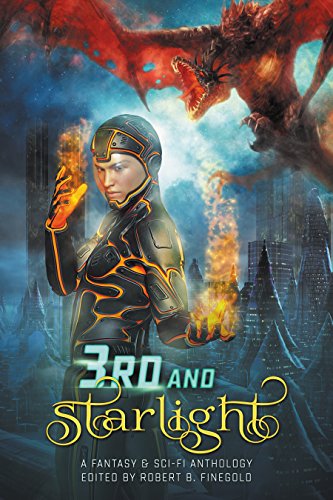

Third and Starlight is finally on sale. Yes, the anthology you've been waiting for if you missed the first opportunity to read my story 'The Waiting Room' in Flame Tree's 'Chilling Ghost Stories' anthology of 2015!

This book is rather special, since all its contributors are finalists or semi-finalists in the Writers of the Future Competition. Never having quite cracked the final eight in that competition I can tell you it's not an easy thing to do. Those who achieve this distinction really can write. I am honoured that my story should have been included in such company.

'The Waiting Room' was quite an appropriate title for my first ever UK sale. I had to wait quite a while for that one and quite a while for the next one too. Though I've now had a total of eighteen short stories published, (ignoring reprints), this year's 'Heavy Weather' in the Flame Tree 'Pirates and Ghosts' anthology was only my second in the UK.

So, if UK fans of my work actually exist, this year you have two chances to obtain it!

Sunday, 31 December 2017

Wednesday, 20 December 2017

Eligible For Short Story Awards 2017

I'm not sure why I publish this list each year. But in case anyone does want to know what stories written by Philip Brian Hall were published during 2017, here is the list:

| The Hard Stuff | 6300 | SF | Unbound II: Changed Worlds |

| The Ship of Theseus | 7400 | SF | Phantaxis |

| Iron Hail | 4500 | SF | All Hail Our Robot Conquerors (ZNB) |

| The Black Horse | 3000 | Hist F | Strange Beasties (Third Flatiron) |

| Heavy Weather | 4200 | Hist F | Pirates & Ghosts (Flame Tree) |

| Conspiracy of Silence | 1800 | Mod F | More Alternative Truths |

Labels:

best short story 2017,

eligibility for awards 2017,

short story 2017,

short story awards 2017

Friday, 15 December 2017

Nationality and Geography

Considerably to my surprise, my first attempt to produce an answer, as opposed to a comment, on a Quora Question has resulted in over 12,000 views and 1,000 upvotes. In part my surprise derives from the fact that I first published my thoughts about Sir William Wallace on this blog in 2013. For some strange reason it appears more people get involved on Quora than read my blog - well, I never!

Anway, in response to my view that the so-called Scottish Wars of Independence were really an argument amongst competing Frenchmen, one reader suggested that a national element in these wars was undeniable. I replied thus:

Although today we understand nationality as having some sort of link with a geographical ‘home’, it is not at all clear to me that the same mindset applied in The Middle Ages. Let us remember The Dark Ages saw a continual series of great national migrations across Europe, including the Scots themselves who came originally from Ireland and did not establish military control over most of what is now called Scotland until the tenth century. The new Scots rulers imposed themselves on a diverse range of pre-existing peoples, including Brythonic, Angles, Pictish, Norse etc. The contemporary sense of group identity was mostly a function of tribe, and geography relevant only in the sense of the domain that a particular warlord was able to dominate. Fixed ‘national’ borders in the modern sense were not yet established.

Great Norman families held estates on both sides of what is now considered the Scottish border and hedged their bets by supporting both sides when claimants to the kingship of England and of Scotland clashed. De Brus himself changed sides back and forth, suggesting political expediency was more important to him than any principled sense of Scottish nationhood.

In this respect it is interesting to compare him with El Cid, now lauded as a Spanish patriot, who also switched sides more than once. Although the Cid’s successors in the struggle developed the notion that the Moors were foreign oppressors in order to unify their own side, it seems clear the Cid himself did not take that view.

A similar phenomenon during The 100 Years War was able to call forth a French identity distinct from the Norman French overlordship of much territory in what is now France.

I suggest it is more probable in all three cases that the geographical notion of ‘nationhood’ evolved and was deliberately cultivated by warlords during the wars of The Middle Ages and was thus an effect rather than a cause of those wars.

But any historical enquiry is best guided by evidence from contemporary sources. If (as is almost certain) I’ve overlooked some in the above theory, I’m only too happy to have it brought to my attention.

Anway, in response to my view that the so-called Scottish Wars of Independence were really an argument amongst competing Frenchmen, one reader suggested that a national element in these wars was undeniable. I replied thus:

Although today we understand nationality as having some sort of link with a geographical ‘home’, it is not at all clear to me that the same mindset applied in The Middle Ages. Let us remember The Dark Ages saw a continual series of great national migrations across Europe, including the Scots themselves who came originally from Ireland and did not establish military control over most of what is now called Scotland until the tenth century. The new Scots rulers imposed themselves on a diverse range of pre-existing peoples, including Brythonic, Angles, Pictish, Norse etc. The contemporary sense of group identity was mostly a function of tribe, and geography relevant only in the sense of the domain that a particular warlord was able to dominate. Fixed ‘national’ borders in the modern sense were not yet established.

Great Norman families held estates on both sides of what is now considered the Scottish border and hedged their bets by supporting both sides when claimants to the kingship of England and of Scotland clashed. De Brus himself changed sides back and forth, suggesting political expediency was more important to him than any principled sense of Scottish nationhood.

In this respect it is interesting to compare him with El Cid, now lauded as a Spanish patriot, who also switched sides more than once. Although the Cid’s successors in the struggle developed the notion that the Moors were foreign oppressors in order to unify their own side, it seems clear the Cid himself did not take that view.

A similar phenomenon during The 100 Years War was able to call forth a French identity distinct from the Norman French overlordship of much territory in what is now France.

I suggest it is more probable in all three cases that the geographical notion of ‘nationhood’ evolved and was deliberately cultivated by warlords during the wars of The Middle Ages and was thus an effect rather than a cause of those wars.

But any historical enquiry is best guided by evidence from contemporary sources. If (as is almost certain) I’ve overlooked some in the above theory, I’m only too happy to have it brought to my attention.

Labels:

100 Years War,

Bruce,

deBrus,

Eld Cid,

French,

geographical nationhood,

Middle Ages,

Moors,

nationality,

ntionhood,

Scotland,

Spain

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)